17th Lancers

Origin of the Regiment 1759

The decisive battle in the war with the French in Canada occurred at Quebec on the 13th of September 1759. At this battle the British forces, under General Wolfe, successfully assaulted and took the besieged French city of Quebec. In the final stages of the battle Wolfe was mortally wounded. Before he died Wolfe directed Colonel Hale, of the 47th Foot, to return to England with his final dispatches and news of the victory at Quebec.

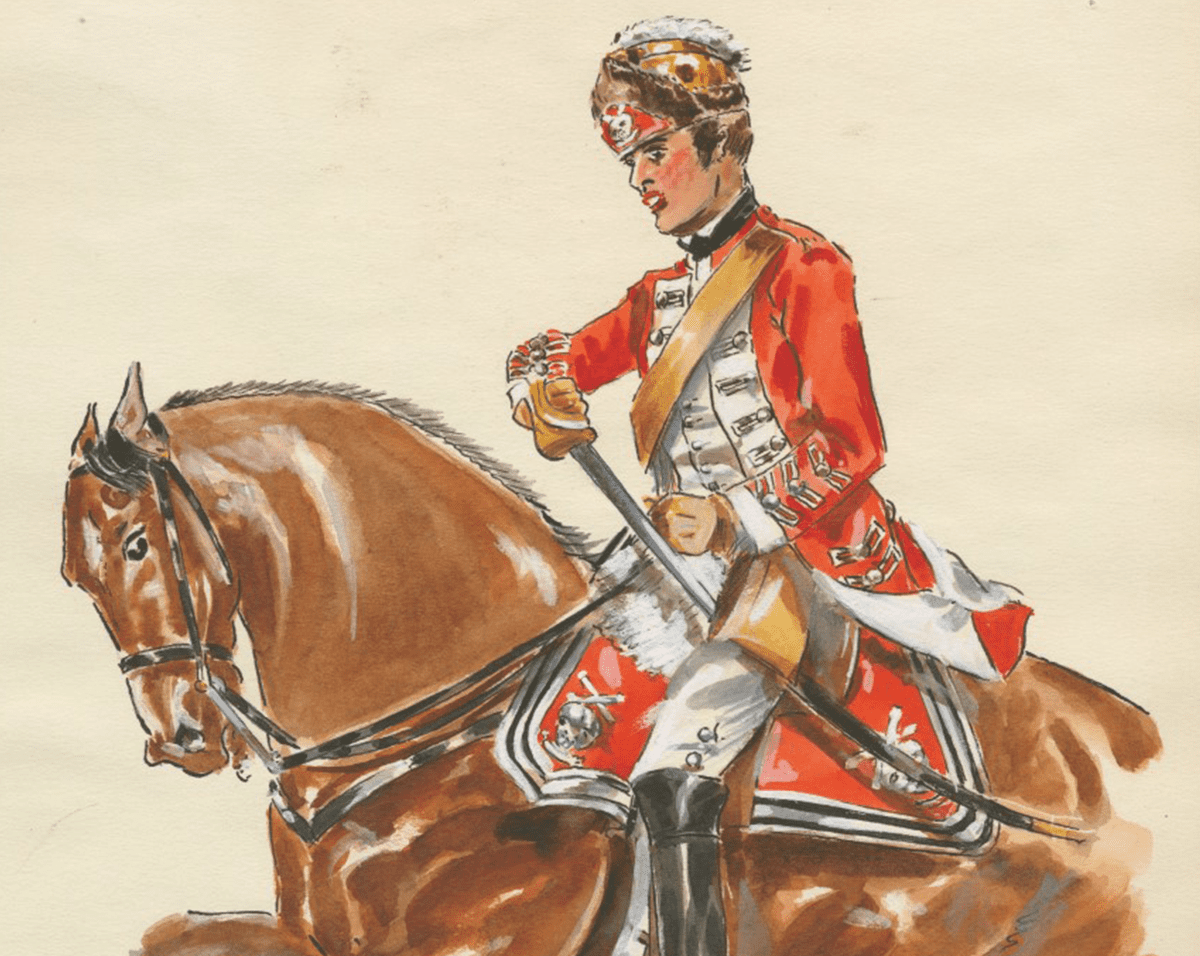

As was normal in such cases, the King rewarded the harbinger of good news. Hale was given land in Canada and a commission to raise one of five new regiments of Light Dragoons. Thus in 1759 the 17th Light Dragoons were born, in Hale’s home county of Hertfordshire. Hale, still in mourning for General Wolfe, chose for a badge the Death’s Head with the motto ‘Or Glory’. This Motto has remained unchanged to the present day, continuing as the Motto (cap badge) of The Queen’s Royal Lancers.

Although raised for the Seven Year’s War, the 17th were not required to serve abroad until the American War of Independence.

The American War of Independence 1775-1783

Initially seven infantry battalions were deployed to the colonies but with the outbreak of general war the need for cavalry was realised with the 17th being the first cavalry regiment selected. The Atlantic crossing took the Regiment two months, arriving at Boston, a city under siege by the American rebels. One week later they were present at the battle of Bunkers Hill. They then re-embarked for Halifax and thence on to the assault and capture of New York and Long Island. In 1777 the Regiment were moved to Philadelphia where they spent the following spring involved in offensive operations around the city only to be evacuated later that year.

Towards the latter part of the war the 17th also provided the only regular British Army element in Tarleton’s Legion with whom they fought until virtually the end of the war. During this period, Private McMullins was carrying a despatch when he was beset by four militiamen – he shot one, disabled another with his sword, and brought the other two back as prisoners. In total the 17th Light Dragoons spent eight years in the Americas; eventually the war was lost as a result of political and military incompetence. The Regiment however distinguished themselves greatly in their first campaign.

On 17th April, 1783, it was Captain Stapleton of the 17th who handed General Washington the final British notice of the cessation of hostilities.

The West Indies 1789

The French revolution of 1789 was to mark the start of 20 years unceasing war with the French. Initially the war was mainly directed against France’s possessions in the West Indies and was to become known as the Maroon Wars. During this campaign the 17th Light Dragoons came under the command of Colonel Walpole. As in the Americas the Regiment was again split up serving as detachments throughout Walpole’s command. As a result they saw action in Jamaica, Martinique, Grenada, and in San Domingo. The Regiment was to campaign in the West Indies for 8 years before returning to England in 1797. Interestingly it was during this period that the 17th gained the nickname ‘Horse Marines’. During the campaign two troops of the Regiment were embarked on HMS Success as this ship was without its own compliment of marines. The crew therefore described them as ‘Horse Marines’ and the nickname stuck. It is also due to this service that the officers of the 17th adopted the naval tradition of not standing for the National Anthem, a practice that continued in The Queen’s Royal Lancers.

South America 1806

The 17th Light Dragoons were not to remain at home for long. At this point of the French Wars, Spain was France’s ally. General Beresford believed that he could inflict on the Spanish what Walpole had managed against the French in the Maroon War. Thus in June 1806 General Beresford captured Buenos Aires, capital of the Spanish colony, and sent word back to England of his achievements and his need for reinforcement. What Beresford however did not expect was that the local population would remain loyal to Spain, the result was that Beresford’s force was quickly over-powered and forced to surrender. Unfortunately the message did not reach England in time and thus in October 1806 a force was dispatched under General Auchmuty to reinforce Beresford; the 17th were part of this force. Auchmuty did not hear of the loss of Buenos Aires until he arrived in South America in January 1807. On hearing the news he landed his force at Caretas Rocks attacking and taking Monte Video, a town containing 160 guns. Unfortunately at this point Auchmuty was replaced by General Whitelocke. Whitelocke proved to be an inept commander and the force was resoundingly defeated when it attempted to storm Buenos Aires. Thus the expedition ended ignominiously with British withdrawal and the 17th Light Dragoons returning to England by January 1808.

India 1808

Within six weeks of their arrival in England the 17th were again warned off for foreign service in India, where the Regiment landed for the first time in 1808. For the next eight years the 17th were employed in protecting the ever-expanding trading interests of the East India Company against the armies of the numerous independent Indian States and Principalities. These were considered a real threat not only because of their training and equipment but also because the French had spent considerable effort wooing them in an attempt to destabilise the British controlled sectors of the Indian sub continent. In 1817 the threat of destabilisation caused by the Mahrattas and the Pindari became so great as to warrant the mobilisation of the entire Army of India against them in a general war. The major enemy of the Regiment during their time in India however was neither the Mahrattas nor the Pindari but disease. In their fourteen years service in India, the 17th Light Dragoons lost 26 officers and 796 other ranks to cholera and other diseases.

Death of Glory

This rare example displayed in our museum shows the cap badge of the 17th in its original form with the crossed bones above the skull.

Balaklava Bugle

Our most prized exhibit: the original bugle blown by Trumpeter Brittain of the 17th Lancers to sound the Charge of the Light Brigade.

Valley of Death

The 17th Lancers rode in the front line of the Charge. o watch our video on the Light Brigade and hear Alfred Tennyson reciting his famous poem, click here.

The Full Story

You can read the full story of the 17th Lancers in The 17th/21st Lancers 1759-1993 by RLV Ffrench Blake.

Home Service 1823 – redesignated Lancers

The Regiment returned to England in 1823. During their passage home the 17th touched at St Helena where they discovered, from an Army List of 1822, that they had been re-designated Lancers. As a result of the success of the Polish Lancers at Waterloo in 1815, the Commander-in-Chief, the Duke of York, decided that Britain too should have a corps of Lancers; the 17th had been selected along with four other regiments to form this corps.

On their return home the newly named 17th Lancers were employed in a round of garrison duties in England and Ireland, which lasted 30 years. In 1826 Lord George Bingham (later Lord Lucan and commander of the British Cavalry Division in the Crimea) bought the Colonelcy of the 17th. The Regiment was mainly employed as an aid to the civil powers though they did provide guards for both Queen Victoria in Dublin and the Czar in Windsor. Bingham spent lavishly on the Regiment buying blood horses for all ranks and commissioning fashionable tailors to produce uniforms for his regiment to his own design. The effect was so drastic that the Regiment came to be known as ‘Bingham’s Dandies’, matched only for splendour by Lord Cardigans 11th Hussars or ‘Cherry Pickers’.

In 1842 HRH The Duke of Cambridge became Colonel of the Regiment. This was the first time in the Regiment’s history that it had a royal patron and it was an association which was to last until the Duke’s death in 1904.

The Crimean War and the Charge of the Light Brigade 1854

It was not until 1854 that the 17th Lancers again found themselves abroad and at war. Russia, under the pretext of a religious dispute in Jerusalem had gone to war against the Turkish Ottoman Empire. In the initial stages of the war the Russians had defeated the Turkish Fleet in the Black Sea. Both Britain and France feared that this might result in the Russian Fleet moving into the Mediterranean, which would have drastically shifted the balance of European power. As a result the British and French decided to mount a joint expedition in support of the Turks. By the time the expedition arrived in theatre the Turks had already managed to lift the siege of Silistria and push the Russians back into their own territory. Although the initial goals of the war had been achieved it was decided by the allies to use this opportunity to destroy the menace of the Russian fleet once and for all by invading the Crimea and destroying the Russian naval port at Sevastopol.

It was during the initial stages of the siege of Sevastopol that the 17th made their most famous charge as part of the Light Brigade at Balaklava. The allies had laid siege to Sevastopol and in an attempt to break the siege on the 25th of October 1854, the Russians launched an attack on the Causeway Heights to cut the British off from their supply chain. Initially the Russians met with success taking both the Heights and the redoubts defending them. The stubborn defence of the 93rd Regiment of Foot and the successful Charge of the Heavy Brigade halted their advance.

Awarded Three Victoria Crosses

It was not until the later stages of the battle that the famous Charge of the Light Brigade took place. In fact it was caused by confusion of orders. From his position on the Sapoune Heights, Lord Raglan could see that the Russians were about to carry away the captured guns from the Causeway Heights. Raglan therefore ordered Lord Lucan, the commander of the Cavalry Division, to launch the Light Brigade to retake the guns. From his position in the valley Lucan could not see the guns. When he asked for further clarification from Captain Nolan, the ADC who had brought the message, Nolan pointed not to the guns on the Causeway Heights, but to a Russian Battery at the end of the valley. Having received the clarification he required he directed Lord Cardigan, his brother-in-law and Commander of the Light Brigade, to advance down the valley.

On orders Cardigan advanced the five regiments of the Light Brigade towards the line of Russian guns at a trot. The first salvo was fired when the brigade had advanced only 200 yards. Each subsequent salvo took a heavy toll on the 17th, who were positioned forward left in the Brigade, but the advance continued unabated with the gaps in the line being filled quickly. As they neared the guns, the Light Brigade broke into a charge, and were met within eighty yards by a final salvo. The 17th, led by Captain Morris, swept down on the enemy, carrying the guns and driving the Russian cavalry, who were massed behind the guns, back in disarray. “Half a dozen of us leaped in among the guns, and I with one blow brained a Russian gunner.” (Private John Vahey, Regimental butcher). The force was however too small to maintain the position unaided and were forced to withdraw back up the valley, again under constant musket and artillery fire from the flanking Heights, and harassed by Cossacks who rode down among them.

Of the 147 17th Lancers that charged, only 38 answered the roll call after the battle. For their gallant actions that day, three Victoria Crosses were awarded to members of the Regiment. Although the 17th remained in the Crimea for the rest of the campaign they did not play a major role in any of the remaining battles, which were predominantly infantry affairs.

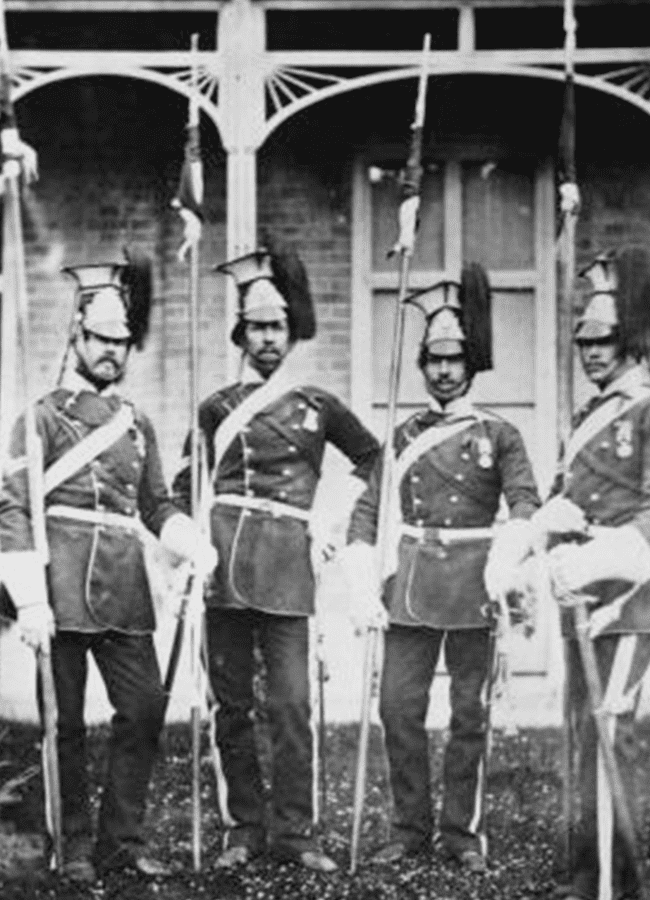

The Indian Mutiny 1857

In May 1857 the Indian Mutiny broke out in Meerut with devastating effect. As a result reinforcements were sent from Britain and the 17th Lancers embarked for this task in October. The Regiment did not land in India until December and were not fit for service until May 1858. By this stage the mutiny was all but over, save for one of the mutineer leaders, Tantia Topi, who was still at large. In order to apprehend Tantia Topi and his followers General Michel was given a force of 1000 infantry, four guns and a squadron of 17th Lancers under Sir William Gordon. The pursuit of Tantia Topi lasted nine months and covered a distance in excess of 1000 miles, 500 of which were covered in a single month. It was during this pursuit that Lieutenant Evelyn Wood (who had transferred from the Navy to the 17th Lancers and was eventually to rise to the rank of Field Marshal) was awarded a Victoria Cross for single handedly attacking a squadron of mutineers from the Bengal Light Infantry. Tantia Topi’s force was eventually defeated; he was captured and court-marshalled in April 1859. The regimental farrier-sergeant assisted in the hanging. The rope with which Tantia Topi was hanged is displayed in the Regimental Museum of The Queen’s Royal Lancers. The 17th remained in India for a further five years before returning to England.

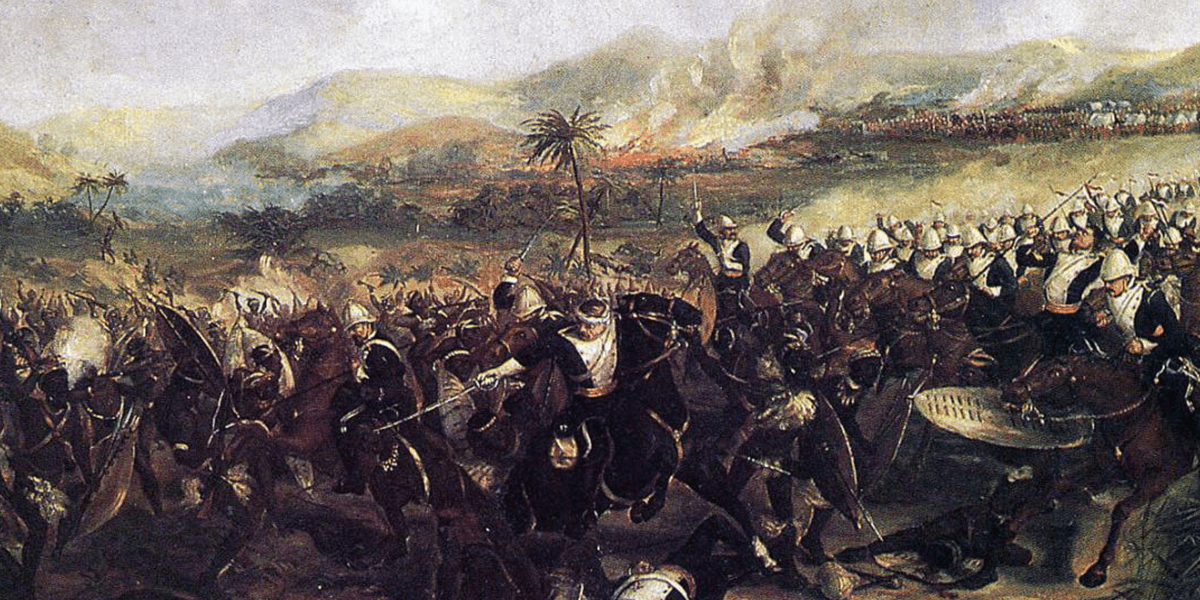

The Zulu War 1879

The next theatre of war for the 17th Lancers was Zululand. In 1879 Sir Bartle Frere Governor of Transvaal was in dispute with Cetewayo, King of the Zulus. Even though the Boundary Commission had found in favour of the Zulus, Frere demanded compensation. Cetewayo refused to concede and Frere ordered an invasion under the command of Lord Chelmsford with a force of 5000 British and 8000 native troops against 40,000 Zulus. Initially the campaign went disastrously with one of Chelmsford’s three columns being routed at Isandlwhana. Immediate reinforcements were called for from Britain and thus the 17th embarked for active service. The Regiment landed in time for the new British offensive starting in July 1879. The objective was Cetewayo’s royal kraal at Ulundi, which the force reached on 4th July 1879. Initially the British infantry squares (containing the 17th) had to withstand a concerted effort by the attacking Zulus. As the ferocity of their attacks slackened, the regiment were ordered to form line and charge. This they did breaking the Zulu infantry and pursuing the enemy for two miles. The effect was so devastating that the Zulu Army never again took to the field.

The Boer War

February 1900 saw the 17th Lancers return to South Africa but this time for war against the Boers. The war had broken out in October 1899 and by the time the Regiment joined the 3rd Cavalry Division all the large set piece battles had been concluded. The Division was employed in the pursuit of de Wet’s Commando in a triangle between Pretoria, Mafeking and Bloemfontein. The most serious action involving the 17th was at Modderfontein where Smuts’ Commando ambushed C Squadron. Although surrounded and out-numbered the squadron refused to surrender. Out of a total strength of 144, 3 officers and 32 soldiers were killed with 4 officers and 33 men being injured.

For the remainder of the Boer War the Regiment were engaged in clearing up operations using the newly introduced ‘blockhouse’ system. In 1902 the 17th returned to Britain, posted initially to Edinburgh and subsequently to Glasgow before deploying back to India in 1905 for a further nine years.

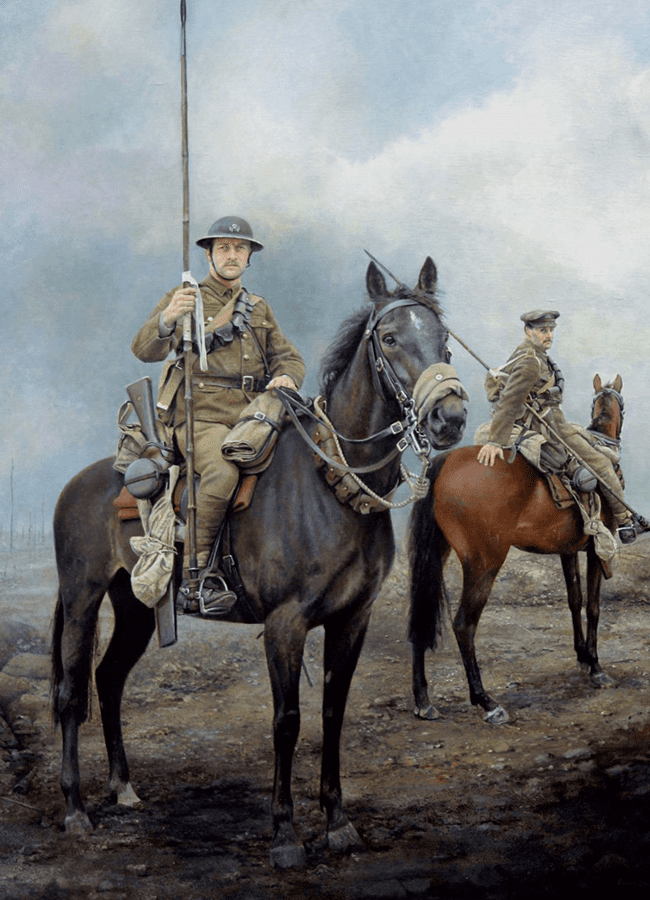

The Great War 1914-1918

The outbreak of the First World War found the 17th Lancers in Sialkot in India. In October, 1914, the Regiment was deployed to the western front as part of the 1st Indian Cavalry Division, arriving in mid-November. By this time the initial mobile phase of the war had become one of static attritional warfare. As a result the 17th spent the following three years taking their turn in the trenches and training for the possibility of an infantry breakthrough which the cavalry could exploit. In early 1918 the Regiment was moved to the 7th Cavalry Brigade. It was not until the German Spring Offensive of that year that the Regiment were allowed the opportunity to demonstrate their mobility and versatility, being occupied in a series of squadron and troop actions, fighting mounted and dismounted and conducting reconnaissance. In the first fifteen intensive day’s fighting the Regiment won one DSO, 6 MCs and 6 MMs. At the end of the war the 17th were posted to Liege in Belgium and from there to Cologne in Germany as part of the occupying army, before returning to England in the autumn of 1919.

Home Service

The Regiment then spent two years in Ireland with the unenviable task of aiding the Civil Power. In the spring of 1922 the 17th returned to Tidworth, where in August they amalgamated with the 21st Lancers to form the 17th/21st Lancers.